As of June next year, when my first novel hits the bookshops, I will officially be both a freelance journalist and a published author – which, frankly, has always been my dream job combo. But in a way, I’ve been doing both kinds of writing ever since I went freelance: wanting to see if I could even write fiction was a big reason for stepping away from a full-time desk job.

I first went down to part-time hours in my job at The Independent on Sunday in 2015; although being an arts and features writer there was amazing in many ways and I was part of the most fantastic team, it was also a very small team and we were all doing about four people’s roles. I was working flat out, constantly, and when I got home at night there was no way I wanted to spend another second looking at a computer keyboard.

I’d also been there five years, and fancied a new challenge. Naively, I thought with that experience under my belt, establishing myself as a freelancer would be fairly straightforward – and give me the time and flexibility to write fiction on the side!

It wasn’t.

Having a part-time job, trying to write fiction, and trying to establish yourself as a new and highly-employable freelancer was way too much to tackle all at once.

But I did, on my freelancing days, start a good habit: I got up and wrote. Maybe just 200 words, maybe 2,000 – but I started those mornings with the novel before even opening my inbox and looking at all my unanswered pitches.

The fictional world I was creating felt like a stream, running in parallel to my not-all-that-successful freelancing career, that I could sweetly step into. Luckily, the words flew out – they weren’t always very “good” yet, but they came. It confirmed that writing fiction was something I wanted to properly commit to.

Exactly a year after taking my first tentative steps into freelancing, I got plunged into it full-time when the Independent went digital and made me redundant. But they also offered money for re-training – and I decided to “re-train” as a novelist, via a Faber Academy course.

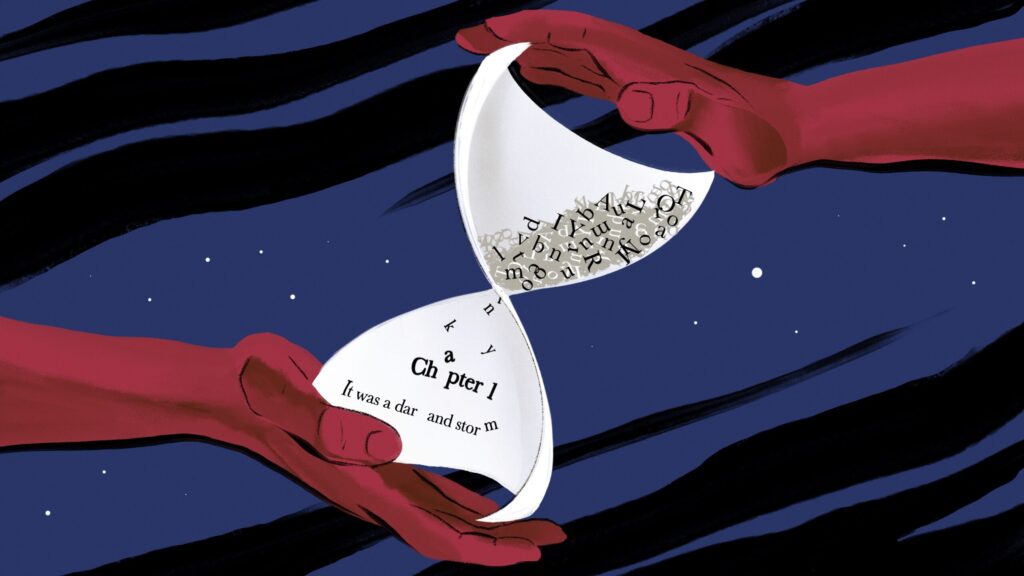

Although being a journalist and being a writer may both be about telling stories, communicating ideas, choosing the best words and editing them brutally, comparing them is like comparing a sprint with a marathon. With journalism, you finish something – decisively, finally – often several times a week or even a day. It’s a fast-paced, fantastically varied, stimulating career. Writing a novel is long, slow, and largely without external validation.

The Faber course helped make writing a novel a bit more like writing for a job. Monthly deadlines for new chapters, feedback from readers, guidance from tutors (usually much more in depth than a newspaper editor’s brusque “this doesn’t work”). It helped me take my writing seriously and to prioritise it, a good habit to get into even in the tricky early days of being a freelancer.

Making a living as a freelance journalist is hard, and I am not brilliant at networking, schmoozing, or having the sort of pushy persistence and thick skin for dealing with daily rejection that are helpful. I suffered a complete crisis of confidence in the early years: was I actually rubbish at the one thing I thought I was any good at? If it hadn’t been for an extremely fortunate living arrangement that meant my London rent was absurdly low for a while, I don’t know that I could have kept going.

But ‘keeping going’ is, it turns out, good advice for establishing a freelancing career (as well as for writing novels). It’s not a quick route to riches, but slow and steady can work: being reliable, being pleasant, always meeting deadlines, gradually extending your contacts, finding and nailing a niche (for me, that was writing about theatre). Eventually, I got to the place where editors asked me to write for them, rather than spending all my time sending ideas to them, to mostly be rejected or ignored.

During those early days of freelancing, having a side project wasn’t an extra stress – it was a release. An escape. If I had no paid work on, I’d work on the book instead. I could trick myself into feeling productive, not a loser. And it reminded me why I was trying to make it as a freelancer in the first place – because I wanted to set my own schedule, to have time to work on my novel.

As I got more successful as freelancer, I got busier, and time on the book got squeezed. ‘Never turn down paid work’ is a freelancer mantra for good reason – you never know when you’ll hit a quiet patch; you don’t want to put employers off. When you are paid per piece, it’s hard to shake the mentality of saying yes to everything.

Trying to make time for a creative project forces you to face your finances – often, I just couldn’t afford to turn down work – but it also brutally confronts you with your real priorities. Basically, you have to want to write more than you want to make more money!

I eventually finished my book, then spent a couple more years squeezing re-writing and editing into mornings, holidays and odd quiet periods. In 2018, I started to work on a second novel, to try to remind myself why I even wanted to be an author. Because there were certainly times when all this certainly felt like added pressure – just another thing to do on the endless to-do list! – rather than a joy.

Writing a novel is a long game, and a long gamble: many people, like me, write books that never get published, so enjoying the process is important. I don’t feel too bad about my first attempt remaining in a drawer; it was the book that taught me how to write.

I was signed to the RCW literary agency for book two instead, and my agent Tristan Kendrick helped me work on finishing it. Once more, this kind of external support helped me prioritise my writing, to treat it more like paid work.

Horrid to say, but the pandemic helped too. Freelancers were first to be cut by publications suffering instant loss of ad revenue in March 2020. I had literally zero work for a while. Rather than panicking, I decided to use the quiet time to finish What Time Is Love? Again, it was amazingly helpful to have something else to focus on when my career was capsizing.

I sold What Time Is Love? as part of a two-book deal. It would be a perfect excuse to ditch the freelancing, if I wanted to – but I won’t. I’m basically ridiculously lucky in having two jobs I love. I’ve had to cut back on the journalism to make more time for fiction, I don’t think I will ever want to wave goodbye to it completely.

It’s good for my brain to have the quicker satisfaction and sense of achievement that comes from finishing an article, as well as the slow-burn pleasure of working on a novel. They compete for your time – but they also complement each other.

Holly Williams is a journalist and critic writing for publications including The Observer, The New York Times, The TLS, The i, and BBC Culture, among many others. What Time is Love? is published by Orion in June 2022. She lives in Sheffield.