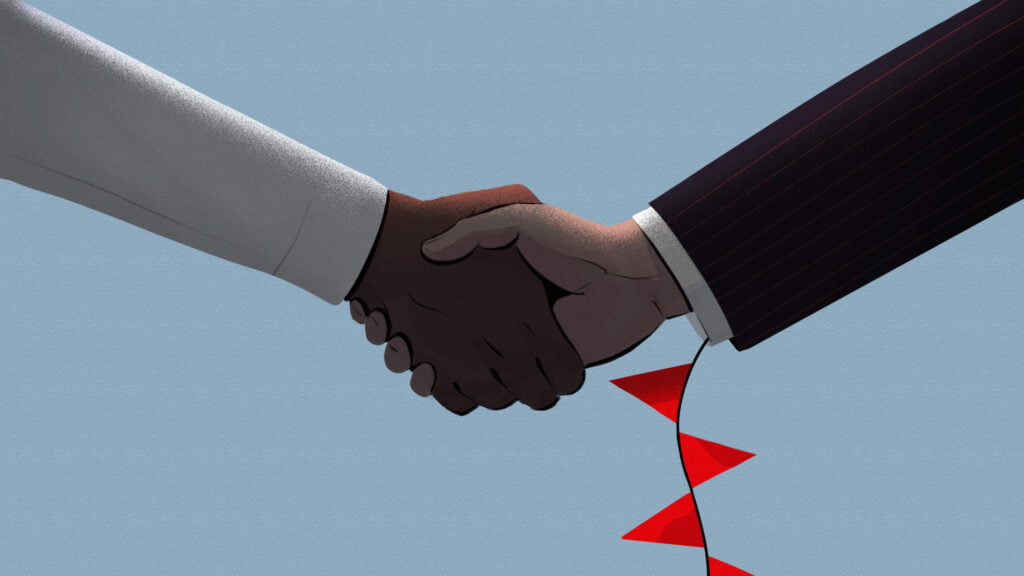

Recently, I received an offer in my inbox to take on some translation work. The offer came unprompted, at a time I needed it, so I welcomed the opportunity. It didn’t have a timeframe, or even a scale of how much work I’ll receive. I thought it would all be quite casual.

Until I saw the contract I was asked to sign. It contained no less than 19 pages. I’d have to spend a day just reading it and making sense of it all.

However, I never sign a contract without reading it. While I’ve never had issues with clients’ contracts in the past, it’s always best to be safe. A contract of this length has many opportunities to hide something that can come back to bite you.

As I know my attention span always drops towards the end of a long read, I reached out to some contract experts. I wanted help understanding the clauses that could potentially harm me, so I could pay most of my attention there. They provided me, and you, with several red flags that could come up in freelance contracts.

Unreasonable non-compete clauses

“I remember an agency asking me to sign a contract with a non-compete clause buried in the fine print,” says Andrew Latham, a Certified Personal Finance Counselor at Supermoney. “It said something along the lines of ‘The freelancer will under no circumstance approach nor compete for any client’s accounts without written consent from the agency.’”

When Latham received this contract, he was already working with several agencies, as well as developing his client portfolio. This clause was unacceptable. “I had no idea who their clients were or who their clients would be in the future,” he adds. The company explained that it only applies to poaching clients he was working with through the agency. However, Latham still insisted they change the language to make it clear.

Companies are quick to include non-compete clauses to protect their business. But as a freelancer, who may be used to juggling several clients, this could be very detrimental. Especially if you work in a niche industry.

“For one of these clauses to be enforceable, they need to set out reasonable terms. That includes the time period, geographical area and industry or type of work,” clarifies Benjamin Rose, a solicitor at Acumen Business Law. You may consider accepting this clause if, for example, you don’t plan to work with that industry in the future. Or maybe the non-compete is about Australia, and most of your work comes from the UK. But “you should be especially mindful of this when you’re undertaking work for a short period, for example, 3 months.”

Who’s the intellectual property owner

“By law, the creator of a piece of work, such as a song, software, painting, book, image, or writing, will be the legal owner; unless they are an employee or it is assigned in writing,” Rose explains. Intellectual property ownership is not an alarming clause by itself, it only becomes a red flag in certain circumstances.

“If you offer a very similar service and have certain standard pieces of work, you will not want to assign ownership of this to the company,” Rose says. For instance, if you’re a leadership coach, and offer training booklets that you wrote, those should remain as your property. Otherwise, you won’t be able to use them with other clients. “Instead, you should seek to only grant a licence to use such materials.” However, if you’re hired to create something bespoke for the company, like a logo, you don’t need to keep the ownership.

Another example comes from writing. If you write a blog post for a company, to help promote their services, you shouldn’t have a problem giving up ownership. But if you write an in-depth expose for the New York Times, about something that you see turning into a book or a movie, you should reserve its intellectual property ownership.

Indemnity and liability

A natural continuation to ownership is the indemnity clause. “These typically make you liable for any damages, penalties, fines, or legal expenses claims that arise from your work,” says Latham. “It’s particularly unreasonable when the clients own the rights to the work and can make any changes they see fit without consulting with the author or creator.”

It can be good practice to buy indemnity insurance, just to protect yourself from any legal action. Some contracts even require that. But this should come in addition to getting rid of potentially harmful indemnity clauses.

“Never agree to a contract with an indemnity clause unless you have complete control over the final published version,” Latham adds. “Otherwise, you are agreeing to carry the liability of somebody else’s work.”

Don’t agree to endless revisions

Every freelance project is bound to receive feedback. When you start your work with a new client, you’ll never get everything right straight away; especially if you’re a creative freelancer. But this doesn’t mean that you should continue revising numerous times until the client is satisfied. You may even find yourself working with different departments where everyone has to have an input or with two founders who are in a power struggle.

Often, contracts don’t include a revision clause at all, meaning, you can be denied payment until you get the job just right. At other times, they may include an unreasonable number of revisions. Your best-case scenario is a clause that suggests you will only commit to two or three revisions, and anything after that requires an additional fee from the client.

Pay close attention to the payment terms

Your eye may wander to the payment side of contracts first, as we all know that credit doesn’t pay rent. But you should also pay close attention to when and how you’ll be receiving the payment.

“How long after an invoice is a payment expected and when invoices need to be presented are the two key points,” Rose stresses. Some people may offer same-day payment, while others will insist on 30 days. For writers and translators, for instance, it’s common to receive payment 30 days after publication, and not just submission, which can often be delayed.

You should take all of those into account, not just to better control your finances, but to also ensure the project is worthwhile. “A large project may require an upfront fee to enable you to provide the services, such as where you need to book a recording studio,” Rose adds. “It is important to have the correct payment structure agreed in the contract to work for the project and you personally.”

It’s not all or nothing

Just because you encounter these red flags, doesn’t mean you have to pass on the project. “Asking for contract changes can be challenging when you need the money, and you’re worried they will go with someone else if you make a fuss,” Latham says. “But remember that most of these clauses are part of boilerplate contracts, and clients will usually agree to reasonable edits to broad and overreaching clauses.”